Eyes Wide Shut was heavily criticized when it debuted in theaters in 1999. Like most of Stanley Kubrick’s projects, it’s a movie that a large portion of viewers didn’t get. Sometimes if the meaning doesn’t hit us over our heads with a golden hammer and we have to think about it even a liiiiiiiittle bit, our interest wanes fast. There are the straightforward entertainment seekers, but understandably, the artistically-appreciative also have their days of wanting to sit back with non-stop action, direct storylines, and time frames that won’t disrupt a short attention span. But whatever one’s preference, a lack of understanding or even utter distaste just means that Eyes Wide Shut isn’t for everyone, rather than “it’s so stupid because I don’t get it.”

Still, it’s okay not to get it. Or like it.

Bill (played by Tom Cruise) is a well-off doctor who purposefully lives in ignorance of the evils masquerading within reach of his charmed life, which he thinks is a Claude Monet painting where his wife, Alice (Nicole Kidman), notices no man besides him unless she says otherwise, people mean well as long as he doesn’t inquire further, and everything around him is as neat and tidy as the package it comes in. But after a disturbing admission from his wife, Bill wanders out for a night full of detours that will warp his perspective on whether ignorance really comes without a price.

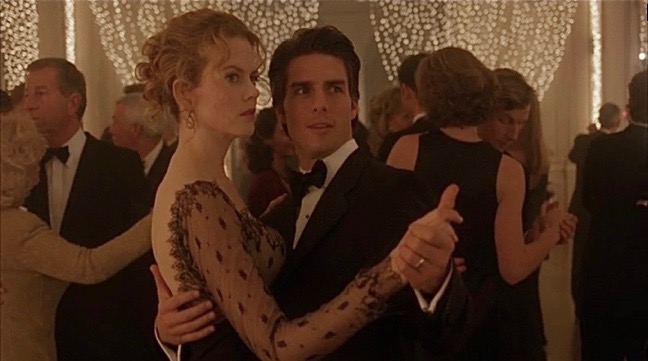

Eyes Wide Shut begins with Bill and Alice heading out to an extravagant Christmas party at the home of one of Bill’s wealthiest clients, Victor (Sydney Pollack). Alice asks Bill if he knows anyone else at the party, to which he responds, “Not a soul.” When she then asks why Victor invites them every year, Bill proudly announces, “This is what you get when you make house calls.”

But it’s quite an eventful night for a couple of outsiders. We’re introduced to the desirability of both when two gorgeous women (Louise J. Taylor and Stewart Thorndike) who likely steal the attention of every man they approach take a keen interest in Bill, and a handsome, older man (Sky du Mont) captivates Alice with his seductive charm. But before either can make their way back to each other, Victor calls Bill upstairs to tend to a medical emergency that Victor wants kept quiet – from his wife (Leslie Lowe) and pretty much everyone. (Bill should step out of his Monet and pull an act of moral superiority on Victor, but the party invites are nice, aren’t they?)

Fast forward to the following night, where Bill and Alice get high in their bedroom and have an argument that stems from Alice’s sudden hostility and insistence on twisting Bill’s words when she questions his fidelity. Desperate to make a point, Alice tells Bill that her own fidelity isn’t so sound – an odd response to him telling her he trusts her, but the entire quarrel is odd, so why wouldn’t this part be, too?

Bill, too astounded to speak, gets a call that a client (Kevin Connealy) has passed and is thankful for the excuse to get away from Alice and clear his head. But maybe he should have stayed home. Or maybe Alice shouldn’t have opened her mouth to begin with.

The slippery night begins with an awkward encounter where Bill’s late client’s married daughter (Marie Richardson) professes her love for him, sending Bill rushing back out onto the cold streets of New York City, where a prostitute (Vinessa Shaw) who lures him up to her apartment, an old medical school buddy turned pianist (Todd Field) who too easily allows Bill to extract the address of a super secret event at which he’s about to perform with a blindfold on, and a costume shop owner (Rade Serbedzija) and his sexually-charged teenage daughter (Leelee Sobieski) each play a careful role in the rubble that awaits Bill’s exit from his final stop.

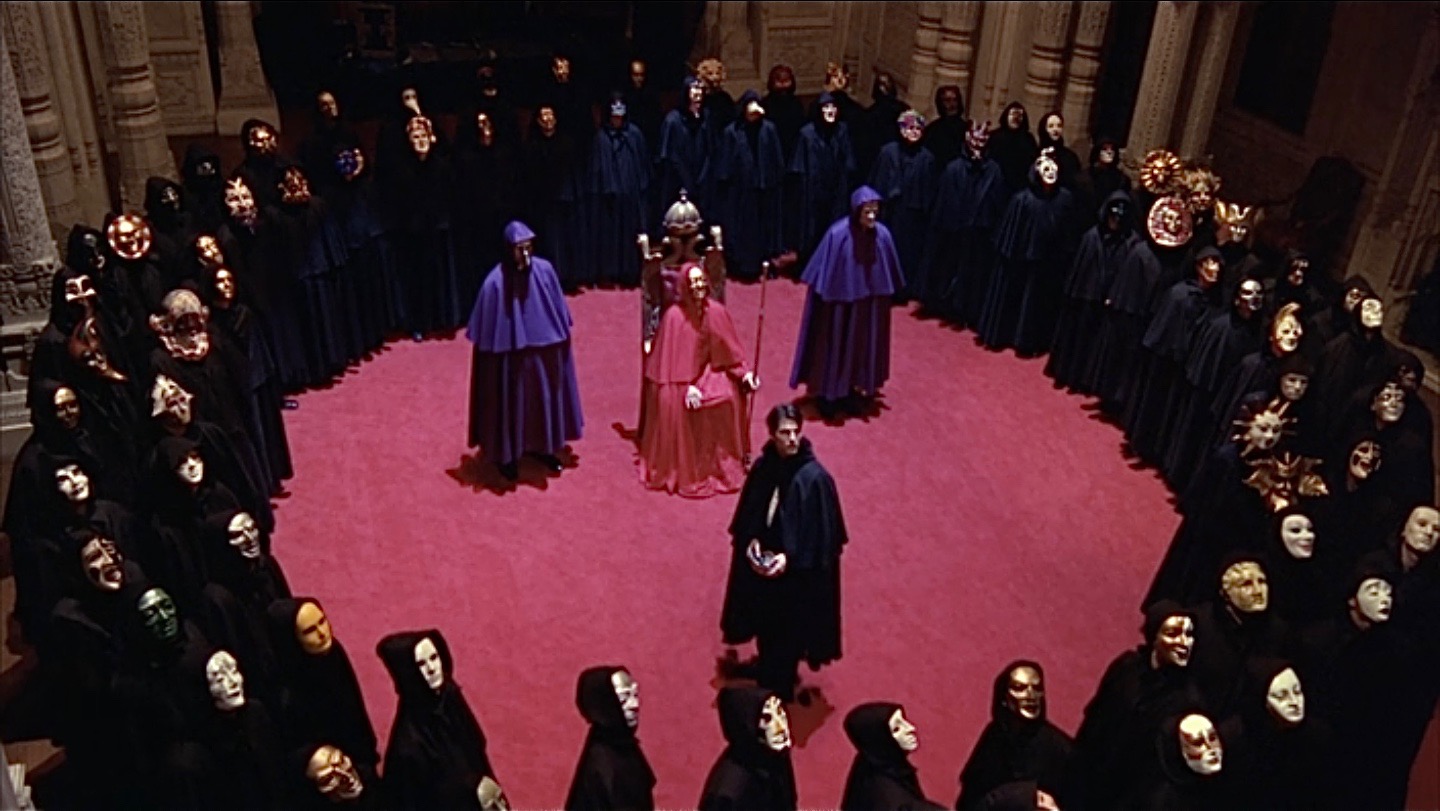

Bill pulls up to the mansion of all mansions, which hides behind two guards, an electronic gate, a very long driveway, and a password that he got from his pianist friend. And no joke, Bill’s grand arrival in a yellow taxi that he hailed from the city streets doesn’t make him feel anywhere near as out of place as he absolutely 100% without a doubt is. If he didn’t want to sound any alarms, he’s not off to a great start, but Bill is forever like a kid in a candy store that eats from the bins and has no idea when he’s long overstayed his welcome – so he thinks he blends in splendidly. And he knows the password, so he’s granted entry after assembling himself in his black cloak and mask that covers his entire face, only allowing for sight and breath.

What Bill sees goes beyond anything his imagination conjured. His friend warned him to be amazed, but, all things considered, his friend sounded more like a child rattling on about a theme park than he did a grown man set to attend a ritualized orgy where countless masked women wander the grand halls and stadium-sized ballrooms fully nude and fully willing to have exhibitionist sex with whichever men desire them. But the festivities have barely begun before Bill is warned by one of the masked women (Abigail Good) that he’s “in great danger and must get away while there’s still a chance.” Since he’s too naïve to take her advice, Bill tells her that she’s mistaken him for someone else and veers off to give himself an eye-opening tour.

It only takes Bill a few minutes to realize that when someone tells him he’s in danger and he needs to run, he’s in a danger and he needs to run. After a terror-stricken moment that could have left him bruised, bloody, dead, or, with luck, just a tad embarrassed, he’s fortunate enough to escape but not fortunate enough to outrun the consequences. His not-so-graceful departure stirs his anxiety that whatever he just witnessed strays far outside the parameters of normalcy that even the most elite of the elite partake in.

Bill tries to make sense of it all by making too much noise (for once in his life) with questions and persistence that don’t bode well with those his questions and persistence threaten to unmask – literally. But even after receiving threatening notes, eying a stalker who makes it a point to be seen (he seriously all but waves), and noticing that people are disappearing or dying, Bill keeps prying. These people go to great lengths to keep their orgies a secret (as if rich people don’t have orgies all the time), and Bill wants to know what the heck is going on.

Bill is on a quest to find out. Whether or not that’s a relief is relative. He’s book smart, but his street smarts (or lack thereof) are what got him here, so our faith in him is hard to conjure.

And for real, what the heck is going on?

Despite prolonged scenes and drawn-out dialogue that some will find frustratingly boring, others will find intrigue in Eyes Wide Shut’s ability to hypnotize viewers with a hunger for what’s about to happen at every given moment the entire 158 minutes through. Hanging on every word and tracking every movement is constant while also fighting to break away if Stanley Kubrick’s eccentricity just isn’t your thing.

Kubrick’s always got something to prove, and this time it’s highly regarded as his recognition that the wealthiest people rule the world and cover up their wrongdoings, using any and every resource to make their hands appear clean. But…not quite. That’s too obvious of an underlying theme for Kubrick, even in a film made over two decades ago.

So let’s break it down.

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD

Bill stumbles upon a secret society of powerful men who anonymously satisfy their carnal urges by having masked orgies with prostitutes. Victor, it turns out, is one of the head honchos for these rituals, and the shame the prostitutes symbolize is hidden away upstairs at his Christmas party, where discretion is demanded from Bill after he saves an overdosed prostitute’s life. Why the need to symbolize shame? Because Kubrick was pointing at something bigger than ritualized orgies with willing prostitutes, which aren’t all that shameful in comparison to his metaphor.

The random encounters throughout the movie aren’t random; they’re hints. Bill meets a prostitute named Domino who takes him to her apartment and settles into her bed beside a stuffed toy tiger (a seemingly out-of-place encounter). When he leaves, his pianist friend points him in the direction of the grand event, which he tells him he’ll need a cloak and mask for. While renting a costume for the event, Bill happens upon a bizarre situation where the costume-shop owner finds his young daughter in a compromising situation with two adult men, whom he locks in the room until he can finish up with Bill and then call the police. When Bill returns the next day to return the costume, the shop owner’s daughter appears with the two men from the night before, who obviously spent the night. When Bill asks why he didn’t call the police, the shop owner claims they came to an agreement instead and that Bill should let him know if he’s ever interested in their other services. All the while, the teenage girl stares seductively at Bill.

Well, that’s interesting.

And then Bill decides to pay Domino another visit. But she’s not home. Her roommate, Sally (Fay Masterson), however, informs Bill that Domino got a call that morning and was told she’s HIV positive. (Good thing Bill didn’t sleep with her, eh? No, loyal Bill left because he couldn’t bring himself to cheat on Alice.)

Initially the question of Bill’s fidelity was left dangling when Victor had him pulled out of a tempting situation to attend to an overdosed prostitute, but by the movie’s end, the question is answered. He allows himself to be tempted, but he doesn’t allow himself to give in. Not even after his wife admits that she would. Whatever Bill stumbled upon the night before, and whatever his intentions, his decency and good will are difficult to refute.

(It’s hard to discern what Bill was supposed to do with his wife’s admission in the hours that followed and if he can now ever look at her – and their marriage – the same. And if he can, how?)

Unfortunately, unlike Bill and Alice, Domino doesn’t come out of her situation unscathed. Instead, it hands her certain death.

But Kubrick’s main point keeps on mounting when Bill, his wife, and his little girl stop in the middle of a toy store directly beside a display of at least 10 stuffed toy tigers like Domino’s, signifying a link between prostitutes and children in the film. And directly afterwards, Bill’s daughter, Helena (Madison Eginton), follows the two men in the background around the corner of the aisle, and that’s the last we see of her. That wouldn’t seem too odd, but these two men were also seen early on in the movie at Victor’s party. Add all that up and it’s curious why these two men showed up in the background at a toy store and exited the scene with Bill’s little girl at their heels.

Popular speculation by fans of Stanley Kubrick has been that the party of orgies in the film represents parties in Hollywood where child actors are introduced to the world of powerful pedophiles, and many of these child actors’ lives fell apart as a result. (Domino’s positive test results for HIV and Mandy’s fatal drug overdose during Bill’s “investigation” are two indications.)

And Stanley Kubrick wasn’t “allowing” (as some have put it) the rich and powerful to get away with it; he was showing the world that that’s exactly what was happening. With former child actors like Corey Feldman, Elijah Wood, and Ronan Farrow having recently come forward to say this is exactly what happened to them and/or the child actors they worked with (e.g. Corey Haim, Nicole Eggert, Alex Winter, Dylan Farrow, Samantha Geimer, and Todd Bridges) when they entered the industry, how is Kubrick wrong or stupid? Kubrick was always determined to expose the ills of society through his work rather than produce mere entertainment for the masses. That’s the type of artist Kubrick was. I think he succeeded with this one. It’s too bad his artistry doesn’t appeal to the mainstream.

Watch on Hulu

https://www.hulu.com/watch/02010788-317e-46ed-8703-df4869d90342